The state of United States museums due to Covid-19: individual perceptions of institutional fiscal security and personal safety

C.L. Kieffer, PhD

The Museum Review, Volume 6 Number 1 (2021)

Abstract The Covid-19 pandemic has greatly impacted the international economy and employment. Some of the hardest hit organizations include small nonprofits, including many museums, which have closed their doors due to pandemic-related lockdowns. While numerous museums are currently reopening, damage has been done to the museum sector and its employees. This article explores the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on museum staff members. 160 museum employees, primarily located in the United States, responded to survey questions regarding their perceptions of insecurity. Results indicate that perceptions of fiscal impact correlate to 43% of respondents who are considering leaving the field. While data indicates that museum employees feel physically safe, the responses to open-ended survey questions indicate possible solutions that museum administrators can take to help mitigate deep-seeded insecurities regarding the future of U.S. museums.

Keywords Fiscal impact; perceived safety; pandemic; job security

About the Author C. L. Kieffer was awarded her PhD in anthropology and awarded a second master’s degree in museum studies from the University of New Mexico. She has almost 20 years of experience working in museum collections and curation at the Autry National Center, the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Museum of Indian Arts & Culture, and Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Kieffer is adjunct faculty at the University of New Mexico and at Santa Fe Community College. In addition to her archaeological research interests, her museum interests include large scale collections moves, repatriation, and collections digitization and accessibility.

Introduction

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, numerous challenging issues have arisen across the international museum sector. These issues include reduced museum budgets, limited facilities, furloughed staff members (Stokes 2020), laid-off employees (Struck 2020), and the potential that one third of U.S. museums will shutter permanently (Durkee 2020). In July 2020, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) released a snapshot study of museums during the first wave of the pandemic (Dynamic Bench Marking 2020). The research conducted for this article expands on that study with additional questions related to the impact and emotions that have resulted due to the pandemic.

AAM primarily surveyed top-level administrators at accredited museums, and the results highlighted the financial insecurity many U.S. museums now face. Laura Lott, AAM President and CEO, stated “The financial state of U.S. museums is moving from bad to worse…[museums] that did safely serve their communities this summer do not have enough revenue to offset higher costs, especially during a potential winter lockdown’” (Bahr 2020). These concerns have rippled through the museum community, but no survey explored the pandemic’s impact as it was felt across diverse museum departments. The survey that generated results for this article was open to all museum employees between December 23, 2020 and January 11, 2021 in order to create a broader understanding of the current museum climate in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Covid-19 survey results

One hundred sixty museum professionals participated in the survey, representing a wide swath of museum professionals (Table 1) from museums of various sizes and types (Table 2) across 33 U.S. states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Ontario, Canada. A disproportionate number of participants were from Texas (n=12), Massachusetts (n=10), Illinois (n=12), and California (n=15). All other states had nine or fewer participants.

Closures and re-openings

Eighty-one percent of those surveyed indicated that local government mandates dictated their museum closures (Table 3). At that time, 58% of respondents worked for museums that had either reopened once, or multiple times (12%). Most closures occurred in March 2020, with openings ranging disparately over the calendar year. The duration of museum closures ranged from one month to eight months, with the average closure lasting 4.11 months.

Staffing impact

At the time of the survey, 68% of participants had kept their jobs through the pandemic (Table 4). However, more than a third of those surveyed know a coworker who has voluntarily quit since the Covid-19 pandemic began.

Remote work is now common: 17% work entirely remotely, 24% have a hybrid work experience, spending time working remotely with limited museum access, and a larger percentage, 30%, have unlimited access to their museum work spaces. The surveyed individuals indicate further changes in staffing may occur, given 43% indicate they are considering leaving their job.

Museum changes

Almost one third of individuals surveyed commented that they were still closed and thus unable to have visitors. Another third of survey participants has only seen visitor attendance rebound to 50% or less than pre-pandemic levels (Table 5). Only two individuals surveyed (both from historic museums/sites – one in Texas and one in Arizona) indicated that visitor attendance was close to pre-pandemic levels. According to 149 respondents (94%), visitors will most likely be expected to wear a mask upon entering the museum building. Interestingly, 67% of respondents indicated that their museum has its own mask policy, rather than selecting a government mandate, suggesting museums are creating their own policies or had them in place prior to the local government regulations.

These mask policies and mandates may be contributing to the sense of safety that many museum professionals have while at work. Of those surveyed, 56% ranked their safety at work in the museum as a Level 4 (36%) or Level 5 (20%) out of 5. (Figure 1).

Museum exhibitions and programming have seen significant changes. Eighty-two percent of respondents indicated that their museums had made changes to their exhibition schedules due to the pandemic. Similarly, 86% indicated that their museums switched to more virtual programming. This virtual programming appears to leave out many school groups given only 53% said they were still conducting school programming.

A vast majority of those surveyed (81%) are worried about their museums’ fiscal status (Table 6). Donations and sales have been significantly impacted in 59% of respondent museums. (Figure 2). Only four respondents (2%) indicated that there has been no impact on donations and sales.

The pandemic’s fiscal impact due to museum closures and lower attendance numbers does not appear to have moved many museums to selling work from their collections to off-set the budget short-falls. Only one individual surveyed indicated that the museum they work for has done so. (Table 5).

Changes in staffing are indicated by the small number of museum professionals (4%, n=7) who indicated they had already left their museum job since the pandemic began (Table 6). More than one third of those surveyed (37%) indicated staffing changes at their museums by way of co-workers voluntarily leaving since the pandemic began.

Correlations

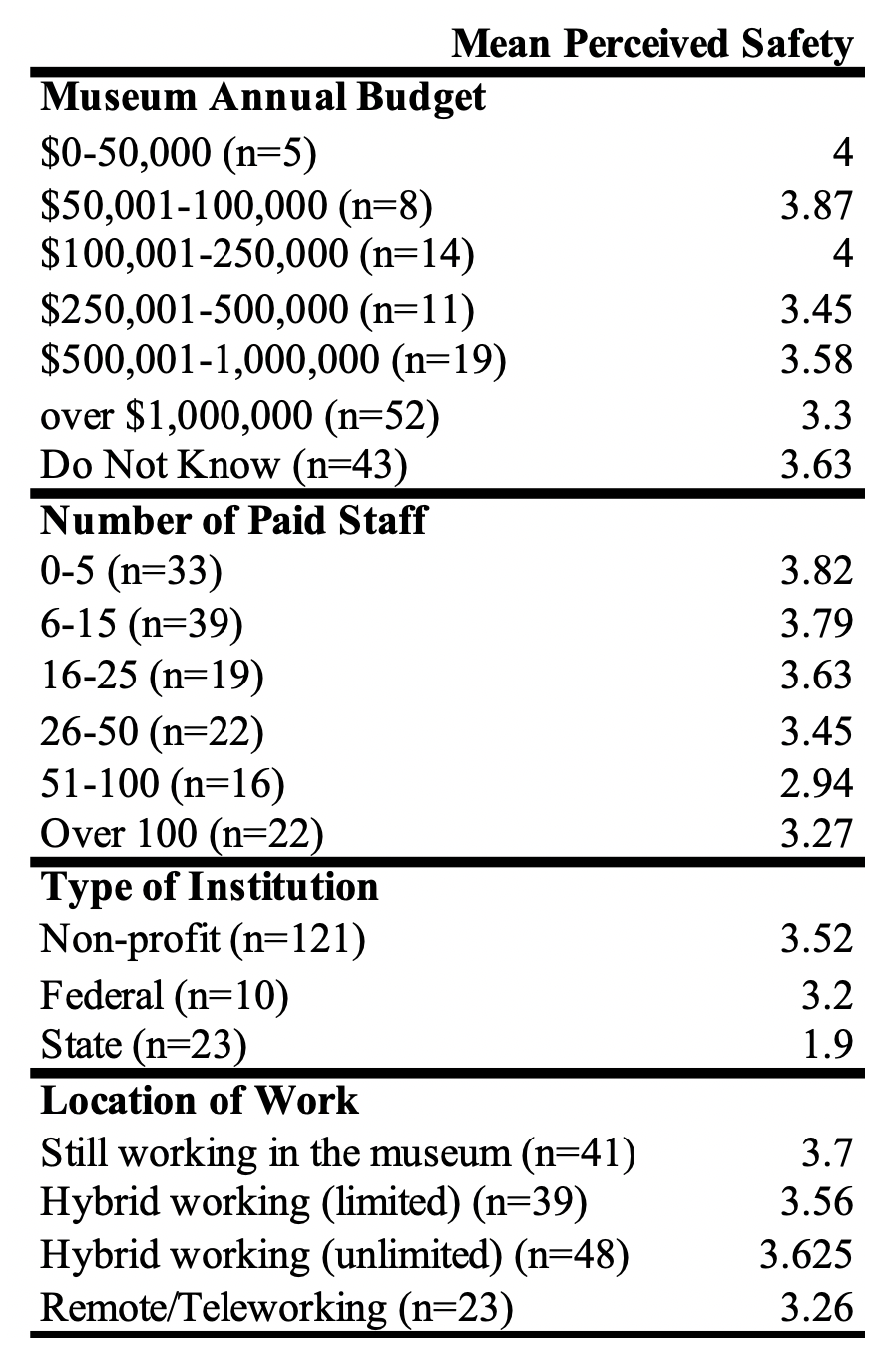

Factors available within the study were explored for possible correlations based on averages of perceived fiscal impact and sense of safety to try to determine which factors may be impacting museum environments during the pandemic. Slight trends of the mean perception of the institutions revenue sources (donations and sales) were noticeable, with those teleworking, working at state institutions , and smaller institutions (both by budget and staff size) having a larger perceived negative impact to revenue sources. Similarly, slight trends of the mean perception of work safety were also noticeable, with those working from home, non-profit institutions, and smaller institutions (both by budget and staff size). However, tests comparing two independent means for these variables could not determine any significant differences as a p<0.05 level. (Tables 7 and 8).

Due to the number of individuals considering leaving their current museum job, regressions based on averages were explored to try to determine a cause from within the survey collection. No major differences between sense of safety for those considering leaving the museum realm (n=67, mean safety 3.54) and those planning on staying (n=81, mean safety 3.64).

There was however a difference between the average sense of financial security between those considering leaving (1.85, n=62) and those not (2.31, n=71). A Z Score of two proportions was run on the 20 individuals with financial concerns out of 84 individuals considering leaving and the 7 individuals with financial concerns out of the 68 individuals not considering leaving. The two-tailed results are highly statistically significant at a p is <0.000001 level.

Discussion

At the time of the survey, museum closure length lasted an average of 4.11 months. While museums in some countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany have received significant support from their governments (Art Form 2020), the United States has not faired as well. As one survey participant stated, “[t]here has been a distinct lack of funding on the federal, state, and local level for museums. We received a PPP loan, but that’s generally been it.”

The fact that museums are turning to the digital realm to engage patrons is no longer news. Numerous journal and news articles have documented virtual tours and programs (Dunn 2020, Gilmore 2020, Gutowski et al. 2020, Haigney 2020), and social media changes. A rare few publications have noted that this increased digital content is resulting in increased private philanthropy (Rich-Kern 2020). This includes one survey participant who noted, “that more people were engaged throughout the pandemic with everything virtual, and in turn donated more when we asked.”

Many of the museums who continued educational programs became creative with new offerings, received support from the Association of Children’s Museums initiative (Howard 2020). For instance, the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis is offering science experiments, fitness activities, virtual tours, story time, and art experiences via their website (Harms 2020). Other institutions are offering expanded teacher resources, curriculum packs, online courses, and alternative field trips, aimed at the nearly 55.1 million school children who have shifted to online learning due to the pandemic (Lewis 2020).

Selling objects is now approved in limited circumstances by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD 2020), but no change was made by the American Alliance of Museums.

Staffing Impact

The data collected from survey respondents indicates that museums need additional funding. Survey statistics indicate that additional funding would go beyond keeping museums running in the short term. Vital funds are essential to creating a sense of job security, and to keep skilled and experienced workers in the museum profession. In the long-term, these experienced and skilled employees are more likely to create innovation and apply change to the workplace (Goulaptsi et al. 2019: 189). At a time when museums are forced to close and visitor numbers have dropped, now is not the time when museums can risk losing innovative employees. Similarly, the best practices in protecting the cultural heritage held by museums is by having individuals with advanced degrees and professionalization (Fifield 2019), these advanced educations help make these individuals more marketable in other sectors, and able to find different employment outside the museum sector. This is supported by the fact that 46% of all job openings projected between 2019-2029 require master’s, doctoral, and professional degree-level backgrounds, and 40% require a bachelor’s degree (U.S. Bureau of Statistics 2020).

Numerous museum jobs required specialized subject area knowledge, including collection managers, yet many are being shut out of their institutions, unable to care directly for the collection. One survey respondent commented on their frustration: “even going into the museum to conduct basic pest management one day out of the week has been denied… I feel upper management does not understand basic concepts about collections management (weekly monitoring of pests, collections security, monitoring environments etc.).” Such lack of care can drastically harm collections in both the short and long term. Previous research notes that the lack of recognition for collection management advanced education and professionalization limits the reach of preventive conservation and risk management best practices in protecting tangible cultural heritage (Fifield 2019).

The large number of museum employees laid off, recently quit their jobs, and those planning on leaving the museum profession should be alarming to the sector. Layoffs at larger institutions have already prompted news stories (Dorbin 2020, Moynihan 2020, Oster 2020, Passy 2020, Sjostrom 2020). While this is the first Covid-19 study to directly ask how many individuals were considering leaving the museum sector, this research is not the first to document underlying changes that motivate the average employee to start looking for new a new line of employment. The Association of Registrars and Collections Managers (ARCS)‘s recent Covid-19 study (ARCS 2021) noted 47.6% of their 462 respondents indicated they had experienced a change to their employment due to layoff, furlough, reduced hours, salary reduction, termination, contract termination, or other such change. The study documented that 20.62% of those already terminated from the museum field were looking into a new career path, while another 8.76% were considering going back to school or looking for a new trade. It is important to note that in the ARCS study, this question only received 88 responses of the 462 survey participants because the question was specifically aimed at those who had been terminated.

A number of surveys have been conducted about the Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on U.S. museums. What is disappointing about many of these surveys is that they are not diving deep into the data they have collected. The AAM (2020) survey and the ARCS (2021) survey report the data on the individual questions, providing easy to digest pie and bar charts. These studies do not assess underlying correlations that may exist within the data. These studies only report the problems and do not evaluate issues or factors that could help to remedy the problems the museum sector faces.

Future changes needed

In addition to the fiscal insecurity that the pandemic has created for the museum field, this study offers insight into other possible reasons why staff have already left or are considered leaving the museum profession. A number of respondents left very poignant responses that should give museum administrators insight into how the field can change in order to help survive the pandemic. These recommendations include:

1. Treat museum staff with sympathy and compassion, particularly in light of cut backs.

- “I’ll miss it but will never go back to it. The way we were all laid off was terrible.”

- “There is a sense from upper management that we should feel lucky to still have jobs.”

- “Our administration has very little sympathy for its workers and will very easily limit hours for full-time staff making far less than the Director.”

2. Find ways to make museum work more meaningful and collaborative, particularly for those working remotely.

- “In periods of sustained remote work, I have considered quitting because I do not have enough meaningful work to maintain my job full-time remotely, and my mental health suffers from both the stress and the isolation.”

- “It is excruciating. We feel forgotten.”

3. Listen to the safety concerns of staff.

- “I am relieved that my work has listened to employees on what would make us feel safe, and have re-closed after the rise in COVID numbers.”

- “I feel like I cannot speak up about safety concerns since I was written up by the interim director after expressing concern about her need to quarantine per state health guidelines. I tried to explain what she was doing was an OSHA violation, but she didn’t listen to me.”

4. Have more transparency and communication within the institution.

- “I feel like my museum does not want to disclose its policies and funds to workers, hence me not being able to answer some of these questions. Therefore, I feel my job is incredibly precarious, but do not know if it actually is.”

- “There has been no effort to communicate with staff; we have had only two staff meetings since the pandemic started (we have a zoom account that can accommodate all staff).”

- “…[A]fter going through the furlough (which had its own confusion and miscommunications), I have a harder time feeling the same level of loyalty and dedication to my institution that I had at this time last year.”

5. Encourage staff to become active in relevant regional organizations.

- “It’s a stressful time but my regional museum association (NEMA) has been amazing.”

6. Reconsider the budget as a whole. Staff want to see greater cuts to boss’ pay (Pogrebin 2020), and many places are already acting accordingly.

- “The Director could take a 50% cut in wages and still be very comfortable compared to everyone else… While salaries are in jeopardy, the organization is moving ahead with a multi-billion dollar building project that features rental space as its main draw.”

- “[S]alaries will be cut at the beginning of 2021. 6% cuts for low-salary employees and 12% for high-salary employees. Administration hopes this is a very short-term measure, but it is the first major impact staff have felt as far as job security.”

Many of these suggestions to improve the museum work environment are not exclusive to the pandemic, and reflect changes that may have been needed prior to the pandemic. One respondent has a clear opinion to why these basic issues have persisted in the museum environment: “We are not comfortable standing up for ourselves and pushing back…for fear of retaliation and gaslighting.” A different survey respondent reaffirms an undertow of preexisting conditions in the museum sector: “[t]he pandemic has taken dysfunction and problems and magnified them significantly.” This culmination of preexisting problems may also contribute to the desire for many current employees to leave the field: “[s]eeing the reaction from the field as a whole has me seriously rethinking the longevity of my career in museums.”

Conclusions

Tens of millions of dollars have already been distributed across many U.S. museums, which has aided in keeping staff employed via the two Small Business Association’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loan programs (The Business Insider 2020). Ultimately, additional funding is required to address museum sustainability through the balance of the pandemic, as perceived fiscal viability of museums by their own staff members.

There has been discussion of changes that museums can and should make to aid in transforming the sector in order to survive the Covid-19 pandemic and to thrive in a post-Covid era (Bull 2020). However, the research contained in this article demonstrates that museums have internal deficits that need to be addressed before innovative sector-wide approaches can be addressed. Museum boards of directors and administrators can better instill staff with a sense of fiscal security for the future of the institution through transparent all-staff communication. This author recommends that when new funds are acquired, such as grants or loans, information be disseminated among the staff to instill more fiscal security and to raise morale. This can only be done with open lines of communication and good leadership. Without addressing staff desires for security and for employee wellbeing, the museum sector may be facing a mass exodus of skilled workers that will be hard, or even impossible, to replace.

References

Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD). 2020. “AAMD Board of Trustees Approves Resolution to Provide Additional Financial Flexibility to Art Museums during Pandemic Crisis.” Press release. https://aamd.org/for-the-media/press-release/aamd- board-of-trustees-approves-resolution-to-provide-additional.

Association of Registrars and Collections Specialists (ARCS), ARCS Member Advocacy Committee. 2021. “Covid-19 Employment Impact Survey Results.” http://www.arcsinfo.org/content/documents/copy of covid 19_employment_impact_survey_full_results.pdf.

Bahr, S. 2020. “Nearly a Third of U.S. Museums Remain Closed by Pandemic, Survey Shows.” New York Times, November 18, 2020.

Bull, J. D. 2020. “‘…Threat and Opportunity to Be Found in the Disintegrating World.’ (O’Hara 2003, 71) – The Potential for Transformative Museum Experiences in the Post-Covid Era.” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 18(1): 3. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.203.

The Business Insider. 2020. “Holograms, hashtags and hand sanitizer: here’s how fine art museums are dealing with the pandemic – aided by stimulus efforts and wealthy backers.” The Business Insider, December 6, 2020.

Dorbin, P. 2020. “Philadelphia Museum of Art slashes staff as pandemic takes its toll.” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 5, 2020. https://www.inquirer.com/news/philadelphia-museum-of-art-timothy-rub-covid-19-20200804.html.

Dunn, K. 2020. “Itching to explore some new museums this season? Here are five virtual galleries to check out.” The Elm. November 19, 2020. https://blog.washcoll.edu/wordpress/theelm/2020/11/itching-to-explore-some-new-museums-this-season-here-are-five-virtual-galleries-to-check-out/.

Durkee, A. 2020. “Covid-19 Pandemic Could Shutter A Third of All U.S. Museums.” Forbes. July 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisondurkee/2020/07/22/covid-19-pandemic-could-shutter-a-third-of-all-us-museums/?sh=547822821d04.

Dynamic Bench Marking. 2020. “National Survey of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums.” https://www.aam-us.org/2020/07/22/a-snapshot-of-us-museums-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Fifield, R. 2016. “Hiring Collections Managers: Opportunities for collections managers and their institutions and allies.” Museum Management and Curatorship, 34(1): 40-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2018.1496355.

Gilmore, J. 2020. “Around Town: Sam Noble Museum creates online presence Sam Noble Home.” Journal Record [Oklahoma City, OK], May 29, 2020. https://journalrecord.com/2020/05/29/around-town-sam-noble-museum-creates-online-presence-sam-noble-home/.

Goulaptsi, I., M. Manolika, and G. Tsourvakas. 2019. “What Matters most for Museums? Individual and social influences on employees’ innovative behavior.” Museum Management and Curatorship, 35(2): 182-195. DOI: 10.1080/09647775.2019.1698313.

Gutowski, P. and Z. Kłos-Adamkiewicz. 2020. “Development of e-service virtual museum tours in Poland during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.” Procedia Computer Science, 176: 2375-2383.

Haigney, S. 2020. “Dizzying Visits to Virtual Museums.” Art in America; 108(5): 21-23.

Harms, K. 2020. “Museum Visits Students Where They Are.” Childhood Education, 96(4): 34-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2020.1796447.

Howard, A. 2020. “Association of Children’s Museums Launches Museums Mobilize to Highlight COVID-19 Responses.” Press Release. https://www.childrensmuseums.org/about/acm-in-the-news/321-museums-mobilize.

Kieffer, C. L. 2021. “Museum Covid-19 Survey Responses (Public Copy)” Unpublished Survey Data. https://www.academia.edu/45053330/Museum_Covid_19_Survey_Responses_Public_Copy_.

Lewis, Z. 2020. Museums at a Distance: Distance Education in the Service of Rural K-12 Educators. M.A. Thesis, New York University.

Moynihan, C. 2020. “September 11 Memorial Lays Off Staff Members and Furloughs Others.” New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast). June 21, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/21/arts/design/september-11-museum-layoffs.html.

Oster, M. 2020.”NY Museum of Jewish Heritage to lay off 40% of staff.” Arutz Sheva/Israel National News [Beit El, Israel], June 23, 2021. https://www.israelnationalnews.com/News/News.aspx/282342.

Passy, C. 2020. “New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art Cuts Staff by 353; The museum projects a $150 million loss in revenue due to the coronavirus pandemic.” Wall Street Journal. August 5, 2020. https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-york-citys-metropolitan-museum-of-art-cuts-staff-by-353-11596656106

Pogrebin, R. 2020. “Museum Employees Want More Cuts in Bosses’ Pay.” New York Times, August 19, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/18/arts/design/museum-leader-salaries-pay-disparity.html.

Rich-Kern, S. 2020. “Museum experience transformed amid Covid: As the pandemic hampers attendance, most offer digital content to compensate.” New Hampshire Business Review, August 13, 2021. https://www.nhbr.com/museum-experience-transformed-amid-covid/.

Sjostrom, J. 2020. “Pandemic forces museum to cut staff.” Palm Beach Post [West Palm Beach, FL], July 24, 2021. https://www.palmbeachdailynews.com/story/entertainment/arts/2020/07/21/covid-19-pandemic-forces-staff-cuts-at-norton-museum/41780027/.

Stokes, B. 2020. “Coronavirus: Museums ‘will not survive’ virus lockdown.” BBC News, April 15, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-london-52215097.

Struck, D. 2020. “‘Poor mummies’: Pandemic sidelines conservators and their care of such museum artifacts.” Washington Post, November 7, 2020.

Torpey, E. 2020. “Education level and projected openings, 2019–29” U.S. Bureau of Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2020/article/education-level-and-openings.htm.

Tables

Table 1. Demographics for 160 survey respondents.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the institutions represented by the survey respondents.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics regarding pandemic shut down and reopening. (*1 institution only opened to staff; **opened to staff only; ***1 of these institutions only opened to staff).

Table 4. Survey results regarding volunteer and staff changes due to the impact.

Table 5. Survey responses related to museum changes to policies, procedures, and programming during the pandemic.

Table 6. Survey responses related to fiscal concerns, and employment changes.

Table 7. Factors that correlate with mean perceived fiscal impact.

Table 8. Factors that correlate with mean perceived safety.

Figures

Figure 1. Survey responses related to the perceived safety of working at the museum since the pandemic has begun (where 1 indicates an individual feeling not safe, and 5 indicates those who feel very safe).

Figure 2. Survey responses related to the perceived impact of museum donations and gift shop sales since the pandemic began. 1 indicates individuals who feel finances have been heavily impacted, and 5 indicates those who feel finances have not been impacted at all.