Poetry makes ‘something’ happen: poetry as captions in memorial museums

Laura Frater

The Museum Review, Volume 5, Number 1 (2020)

Abstract The use of poetry as a means to engage the public with traumatic periods of history has been met with skepticism. Yet, poetry, and language that evokes poetry, is used in major memorial museums in the United States, including the National September 11 Memorial Museum in New York City, and in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. This paper argues that in both these memorial museums, poetry functions as captions alongside representations of trauma that defy language. Poetry operates as a caption in the traditional sense by describing and contextualizing these representations, while also operating as a buffer between the visitor and the trauma depicted through aesthetics specific to poetry. This aesthetics include the “white space” surrounding the poem and poetic structure. Ultimately this paper argues that poetry protects the visitor from collective suffering, while paradoxically bringing the visitor closer to it by using poetry to emphasize the trope of witness, and by turning the visitor into a prosthetic witness.

Keywords Memorial museums; poetry; collective trauma; visitor engagement; exhibition design

About the Author Laura Frater is an Adjunct Instructor of English Literature at Iona College. Originally from Glasgow, Scotland, she holds a BA in English Language and Literature from King’s College London, and an MA in English Literature from Iona College. At Iona, she was the recipient of the Graduate Medal for English. She presented an excerpt of her MA dissertation, “Postmemory, Poetics and the Generation After,” at The Annual Scholars’ Conference on the Holocaust and the Churches in 2018. Frater will begin her PhD in Literature at the University of California at Davis in Fall 2020. She is the recipient of UC Davis’ Provost’s Fellowship. Her interests include memorial museums, collective trauma, poetry and poetics, spaces of commemoration and remembrance, museum visitor experience, and exhibition design. laurafrater97@gmail.com

Despite W.H. Auden’s declaration that “poetry makes nothing happen” [1] (Auden, 53), this paper examines the ways in which the poem functions as a privileged space through which to encounter collective trauma in spaces of public history. Through the lens of two of the United States of America’s most widely known memorial museums (Radia, 88), the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) and the National September 11 Memorial Museum, this paper offers a series of case studies that examine the use of poetry and poetical approaches to language in each museum. Ultimately, this paper contends that poetry in memorial museums operates as captions. Appearing alongside representations of trauma, poetry describes, clarifies, and contextualizes representations that resist language. Poetry performs the conventional roles of the caption while using its special structure and relationship to the “white space” surrounding it to distance the visitor from the full impact of past suffering.

While discussing the poetry of William Heyen including one of his verse collections, Shoah Train, Jorie Graham contends that “in the strongest poems one feels what one needs to feel: the battle between the desire to transform and the resistance of the facts; the frailty and perhaps even the immortality of those horrifying facts becoming a story.” (Graham, 30) Yet, the use of poetry as a way of encountering collective trauma has also been met with skepticism and unease. Susan Gubar argues that in relation to the Holocaust, “the idea of useful or beautiful verse about genocide strikes most people as inane at best, repulsive at worst.” (Gubar, 165) Philip Metres echoes this sentiment in the context of 9/11 poetry: “Poems that take on subjects as public and iconic as the attacks of September 11th risk not only devolving into cliché and hysterical jingoism, but also risk perpetuating the violence of terror, and the violence of grievance and revenge.” Despite these concerns, Cathy Caruth sides with Graham: “It seems to me that the capacities of poetry to be so effective in communicating trauma derive from the fact that they can maintain or can echo those parts of traumatic language just not circumscribed by rationality.” (Caruth, 194)

Poetry in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Christened by President Clinton as a “physical container to preserve the memory of the Holocaust for all Americans” during its opening in 1993 (Linenthal, 1), the USHMM strives “not only to honor and remember victims but also to create a lasting, permanent record of the past … to educate the public about the causes and implications of the Holocaust, as well as to morally educate its audience to work to prevent such atrocity from happening again.” (Sodaro, 31) The museum uses a variety of tropes and devices to engage visitors including familial photographs, reenactment tools and a large array of artifacts. The USHMM also uses poetry, as well as language that evokes poetry, in various parts of the museum including the permanent exhibition and the children’s exhibition, Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story.

“We are the Shoes”

In the USHMM’s permanent exhibition, the visitor enters a windowless room with white walls (figure 1). On each side of the room are piles of misshapen and dirty shoes originally taken from prisoners arriving at the Majdanek concentration camp (Linenthal, 163-64). The shoes are enclosed by three-foot tall glass walls. Above each shoe pile is the same poem excerpt, one in English and one in Yiddish, extracted from Moishe Shulstein’s, “I Saw a Mountain” (Linenthal, 200). In the excerpt, the speaker talks from the perspective of the shoes, noting their origins and why they were spared the “hellfire” (Linenthal, 5):

We are the shoes, we are the last witnesses.

We are shoes from grandchildren and grandfathers,

From Prague, Paris, and Amsterdam,

And because we are only made of fabric and leather

And not of blood and flesh, each one of us avoided the hellfire.

(Shulstein, USHMM)

Shulstein’s quotation pushes the visitor to acknowledge the shoe pile, while simultaneously distancing them from it. The quotation seeks attention: it is presented under a spotlight in large, capitalized, three-dimensional letters that stand off the wall. The USHMM has numerous artifacts, and this three-dimensional aspect of the quotation excerpt not only stands out to the reader, but tentatively turns the quotation into an artifact itself. It becomes as physical as any other object in an object-heavy space. The raised letters (Gentry) of the quotation insinuate a sense of permanency, unlike the silk-screened letters of Hitler’s speeches located in the museum which, as the USHMM explains, “allow for easy removal.” (Linenthal, 200)

In terms of its content, the Shulstein quotation clarifies the scene by operating like a caption to the artifacts below it. The shoes are so contorted that it is initially confusing to decipher them. Yet, the excerpt points directly to what the shoes are in the opening line: “We are the shoes.” The aggression of this statement is heightened by capitalization, and the sharp black font, and grounds the visitor in the scene that is painful to absorb. The “faint, rubber-tinged fumes become more nauseating the longer you stand in the room” contends a USHMM volunteer (Boyle); one cannot help but imagine the shoeless owner, barefoot and vulnerable. However, the poetic excerpt simultaneously gives the reader something to look at: when the shoes become too challenging, poetry offers the visitor the opportunity to look up.

The poem is in part defined by the white space, an absence of language or another visual stimulus, that surrounds it. The white space around Shulstein’s poem is exaggerated and extended, so much so that it threatens to overwhelm the overall exhibit. In the USHMM, text is everywhere, but the white space around Shulstein’s quotation tentatively offers relief, albeit momentarily, from verbalized trauma. It creates a fragile sense of calm that the exhibition disrupts. This absence of language also seems to ask: how necessary is language, let alone captions, when expanding upon representations of trauma?

Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story

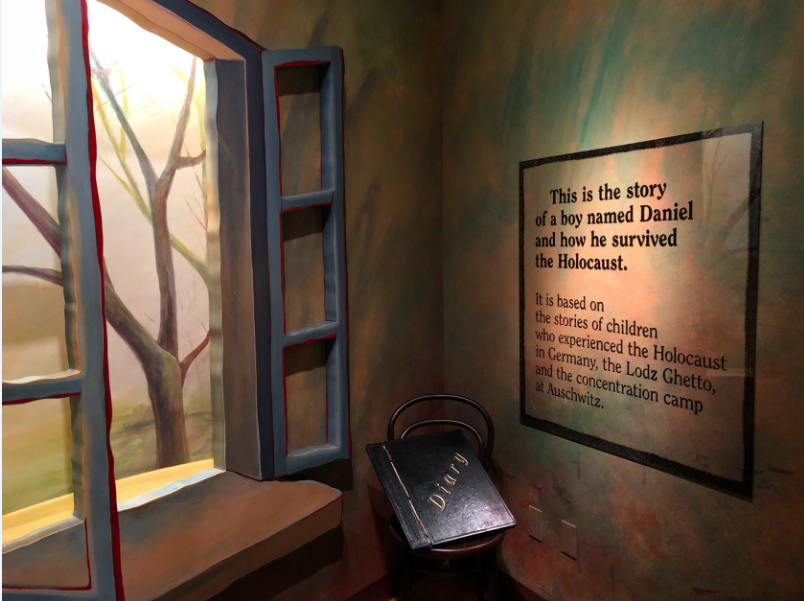

Described by the USHMM’s Exhibition Experience Manager, Ramee Gentry, as one of its “most well-attended exhibitions,” and appreciated in part for being one of the museum’s “less intense” experiences, Remember the Children: Daniel’s Story invites visitors to learn about Daniel, a fictional Jewish boy, and his world pre- and post-Holocaust in a “nonthreatening, hands-on setting for ages as young as eight.” (Solomon) Visitors walk through a series of “sets” including Daniel’s house, his town, and the ghetto and concentration camp to which he and his family are transported. Once visitors have explored this “doctored reality” (Huxtable, 25) they are asked to write down their feelings about Daniel’s trauma and to “post” their reflections to other visitors through a make-believe mailbox. The exhibition uses various mediums of communication including audio and video, Daniel’s “diary entries,” and guideposts displayed under spotlights throughout the exhibition. These ten guideposts, or “signs” (Branham, 44), instruct the visitor to place her attention on particular spaces and artifacts within Daniel’s Story, while instructing the visitor on when to reflect on her personal feelings about Daniel’s trauma. While these guideposts do not read like a typical poem, the guideposts’ text is molded into a poetical structure (figure 2). I will refer to the guideposts as poems throughout the rest of the paper for the sake of cogency.[2]

The opening poem of Daniel’s Story (figure 2) is displayed on a wall as the visitor enters the exhibition. This poem sits adjacent to an “open window” showing a forest landscape and Daniel’s “diary” atop a wooden chair. The poem’s opening stanza summarizes some of the key events of the exhibition’s narrative: “This is the story / of a boy named Daniel / and how he survived / the Holocaust.” While the opening stanza sounds like the beginning of a fairy tale, the language is manipulated to mirror poetic structure. The overall scene, with the diary and the window frame, could be the bedroom of a child writing in his diary before listening to a fairytale – it is “story time.” This opening stanza tentatively asks the visitor to adopt a child’s perspective as she enters the exhibition, while also creating a buffer between the visitor and the trauma she expects to confront. The word “story” fictionalizes Daniel’s experience of the Holocaust, and the revelation that he survives makes his plight less tragic. The enjambment of the stanza highlights key words that may put the visitor at ease entering the exhibit: “story,” “Daniel,” “survived,” and “Holocaust” round out each line, and literally encompass and cushion the opening stanza. The bold font heightens our attention to this.

Aside from the first poem’s opening stanza, the poetry of Daniel’s Story is largely instructional in nature. Some of the poems tentatively ask the visitor to become an extended member of Daniel’s family by encouraging her to explore the intimate spaces of the family home. In “Daniel’s House,” the speaker urges the visitor to explore the storage unit where Daniel and his sister keep their “sports things,” and to “visit Daniel’s bedroom.” The visitor is even asked to “look at the cabinet where / Mother kept the candlesticks.” The absence of the word “their” before “Mother” insinuates that the visitor is another child in the family home, returning to reminisce. The poetry of Daniel’s Story urges the visitor to perform an extended role in this familial structure of remembrance, promoting the “oedipal familial structures” which so often act as “the agents and the technologies of cultural memory.” (Hirsch, 27)

While the poem’s instructions create a tentative intimacy between the visitor and Daniel’s world by encouraging her to perform as a prosthetic family member, the poems also distance the visitor from Daniel’s trauma. In the make-believe town, the light becomes dim: there’s a bench for “Jews only,” anti-Semitic graffiti, and the window of Daniel’s family’s business has been shattered by a brick. Yet, unlike the poetry of Daniel’s family home, the poem of the make-believe streets, “Daniel’s Town,” does not ask the visitor to physically engage with these scenes of trauma. Instead, the speaker instructs the visitor to only “look” and “notice” the Jews-only bench, but not to sit on it. Even as the visitor moves from the streets to the ghetto, the poem “Ghetto Room” allows the visitor to remain distant from the trauma of the new surroundings. “Read a postcard Daniel got in / the mail” and “Look for Daniel and his sister’s secret hiding place,” instructs the speaker. By performing familial activities and the role of the child, the visitor may look away from the more harrowing spaces of the ghetto like the dirty bedsheets and clothes, and the cramped conditions.

When we attempt to connect with the trauma of others, Marianne Hirsch argues that “the images already imprinted on our brains, the tropes and structures we bring from the present to the past, hoping to find them there and to have our questions answered, may be screen memories – screens on which we project present or timeless needs and desires and which thus mask other images and other concerns.” (Hirsch, 120) Hirsch outlines one of the pitfalls of encountering past trauma like the Holocaust: the difficulty in not over-identifying with the pain of others, and thus overwhelming it with emotions and memories of our own. The poems in Daniel’s Story recognize this issue and help the visitor avoid projection and thus the obscuring of Daniel’s trauma. “At the end (emphasis added), you can think about / your own feelings and write down your thoughts,” declares the speaker in the exhibition’s second poem. Yet, before the speaker grants the visitor permission to do so in “Things to Do,” the penultimate poem, “Things to Remember,” asks the visitor, “What happened to Daniel and / his family? / What was the Holocaust?” The poem endeavors to have the reader focus on the trauma of the Holocaust first before exploring their personal reactions.

We never meet Daniel during the exhibition, but his presence is highlighted through the poems. The poems’ titles, which are handwritten, match Daniel’s handwritten diary entries that appear sporadically in the exhibition. While the poems themselves are typed, the handwritten title suggests Daniel’s presence and brings the visitor metaphorically closer to him. The borders around the poems actualize his presence: similarly to a child’s handiwork, the inner border wobbles, and the outer border resembles an uneven, crayon scrawl drawn in a childlike manner.

While Daniel’s presence is reaffirmed through the poems, so too is his role as a child victim narrator. How can we not visualize him as a helpless youth as we are directed through Daniel’s world during the Holocaust? Mark M. Anderson points out the “iconic role” of the child victim narrator within the canon of Holocaust remembrance, contending that “children have consistently proven to be the most moving and believable witnesses” when “representing the Holocaust as a whole.” (Anderson, 2, 1). The child victim, Anderson contends, “transcends history even as it affirms the most dreadful historical reality, it appeals to our own memories of childhood, our identities as parents, sisters, brothers: it speaks to us in existential and moral terms, and only secondarily in historical or political ones.” (Anderson, 3) While Daniel’s Story evokes this universal yet vulnerable image, the poems of the exhibition evoke and undermine it. The typed-up body of the poem clashes with the child’s handwriting and crayon-scrawl borders, as does the authoritative voice of the poems and the references to Daniel in the third person.

National September 11 Memorial Museum

Having now welcomed more than 10 million visitors since its opening in May 2014, the National September 11 Memorial Museum was created with the following four guiding principles: “scale, memory, authenticity, and emotion.” (Sturken, 78) In large part, the former director of the USHMM, Alice Greenwald, led the design of the museum’s exhibitions, along with “museum leaders and advisers; curators, educators, and historians; designers and architects,” who agreed that “the story of 9/11 was, and is still, evolving, its repercussions still unfolding.” (Greenwald, No Day, 11, 12) Given Greenwald’s involvement, it is unsurprising that the 9/11 Museum shares similarities with the USHMM in relation to its aesthetics and choice of visitor engagement tools. “Even the architecture is similar,” argues Amy Sodaro, “[as is the] emphasis on victims, audio and video testimony, multimedia and interactive displays.” (Sodaro, 155-56) Poetry and language that evokes poetry are also displayed in both museums.

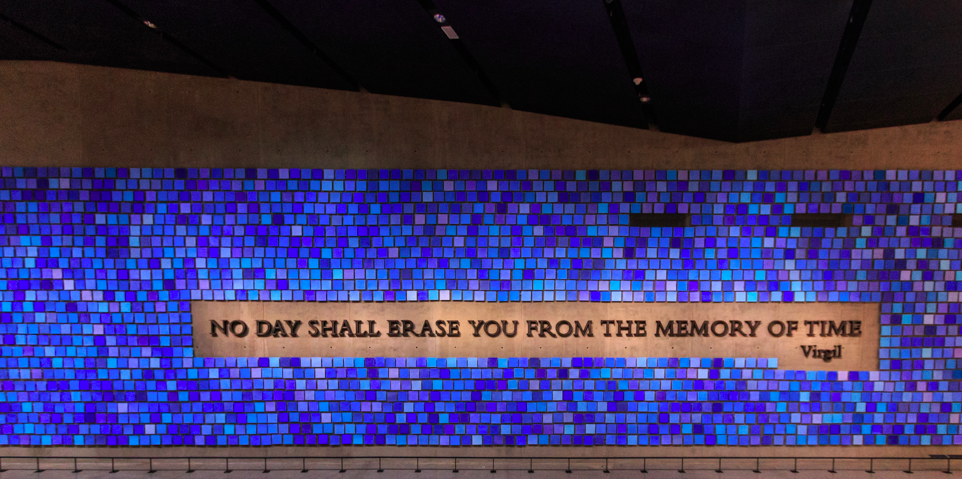

Virgil’s Aeneid

As visitors make their way into the 9/11 Museum’s Memorial Hall, they get a full view of Spencer Finch’s memorial artwork, Trying to Remember the Color of the Sky on that September Morning (2014), displayed across a slurry wall that once enclosed the World Trade Center. This wall now conceals a repository containing the unclaimed and unidentified remains of 9/11 victims. (OCME) Finch’s artwork consists of nearly three thousand individual blue pieces of paper intended to symbolize the victims of 9/11 and the 1993 World Trade Center attacks while referencing the blue sky that became the unusually beautiful backdrop to the September 11 attacks. (Greenwald, No Day, 22) Inserted into the middle of Finch’s work is a quotation from Virgil’s epic poem, Aeneid: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time.” (Figure 3)

Controversy surrounds the context of the Virgil quotation. In the scene from which it is sourced, “Virgil addresses a pair of male lovers after a nighttime excursion in which they butcher their slumbering enemies before being killed themselves. The poet commemorates their deeds and willingness to sacrifice their lives for each other and their cause.” (McGowan, 230) Given this context, the quotation is arguably “more applicable to the aggressors in the 9/11 tragedy than to those honored by the memorial.” (Dunlap) The President and CEO of the museum, Alice Greenwald, defends the use of Virgil’s words, noting that the families of victims expressed “resounding approval” for its inclusion in the Memorial Hall, and for its juxtaposition with the repository. (Greenwald, interview)

Since museum visitors must pass the repository as they enter the museum’s lower level, the design team, Greenwald pointed out, needed to “confront the remains.” (Greenwald, interview) Poetry, she argues, facilitates this experience for the visitor in a “meaningful way” by speaking directly to the 9/11 Museum’s mission of commemorating those who perished during the attacks: “[Virgil’s words] captured what this place is all about; it’s about never forgetting the victims.” (Greenwald, interview)

While the memorial artwork and Virgil’s poetry aims to encourage reflection on the dead, both the artwork and the poem dwarf the small plaque that points to the repository.[3] Virgil’s poetry is crafted from recovered World Trade Center Steel which, Greenwald explained, turns the WTC remnants into “objects of beauty, [signaling to] the transformative quality of memory and remembrance.” (Greenwald, interview) The poem excerpt, when combined with the remains of 9/11 victims, is aestheticized for an audience. The source of its material and the intended symbolism behind the poem’s construction reveals what Hirsch describes as our tendency to project present, or timeless, needs and desires onto representations of past trauma which, as noted on page 8, “masks other unthought or unthinkable concerns.” (Hirsch, 120) Virgil’s poetry intends to mediate remembrance, but in this space of traumatic memory, poetry highlights our desire to beautify past trauma, even if it means contorting evidence of trauma.

While the blue paper of Finch’s memorial work conceals the repository wall, the poem excerpt slices through the paper and exposes the grey concrete reality of the repository. Greenwald notes that the design team did not want to just “pretty up” the repository wall, and poetry helps prevent this by disrupting the jovial blue spread of Finch’s paper. (Greenwald, interview) Similar to Shulstein’s poem excerpt in the USHMM, Virgil’s words are capitalized and three dimensional, casting a shadow across the slurry wall. Against the blue paper, the quotation appears grim and somber, as if to signal to the bleakness of the space in which it exists. The metal barrier encompassing it keeps us at a physical distance.

The ramp

At the head of a ramp leading into the lower level of the 9/11 Museum, visitors pass a photograph showing the World Trade Center minutes before the first plane hit the North Tower, as well as a map and a summary of the four hijacked planes’ movements on 9/11. As visitors pass this combination of text and images, they begin to hear voices belonging to men and women with various accents, all colliding in the dark, creating a quietly chaotic space. The voices recall their locations and their reactions when they witnessed or first learned of the attacks. (Sodaro 145) Snippets of their stories appear on maps of different continents that are projected onto multiple columns. This text on the columns evokes poetic structure. As visitors pass through, more columns appear displaying photographs of witnesses watching the Twin Towers and the Pentagon under attack. (Greenwald, No Day, 42)

Amy Sodaro argues that this section of the 9/11 Museum presents a “coherent narrative” – “As one listens, the visitor realizes that like the map, the voices also converge. What at first seems to depict the multiplicity and fragmentation of individual memories of the day begins to literally form into one coherent narrative: collected memory becoming collective.” (Sodaro, 146) The voices and maps may unite, but the crowds of visitors who routinely try to avoid each other in the dark, and the confluence of accents and different languages delivered orally, generates a degree of confusion which undermines an overall obvious sense of unification. However, the poetically structured slices of text – short, manageable bursts of witnessing – projected onto the columns glow in the dark, providing a point of focus and stability for the visitor. This poetry fades away slowly and reappears slowly; the traumatic recollections do not overwhelm the visitor for too long.

When the final columns appear with photographs of witnesses, the poetry of the previous columns offers potential captions for these “wordless” pictures. The subjects are captured with their mouths open, or their hands over their mouths. Their commonality is an absence of language. But the poetry of the columns attempts to fill these silences with statements like, “It was just / as if time had stopped;” “And everyone / stopped.” In this space, poetry tentatively provides language to images of atrocity that seem to defy language.

The historical exhibition

The museum’s historical exhibition provides visitors with a timeline of the day’s events, as well as historical context prior to the attacks, and 9/11’s continuing implications. Amongst the “artifacts, images, first-person testimony, and archival audio and video recordings,” this section of the museum uses language that resembles “vignettes.” (Greenwald, No Day, 91) These short pieces of “poetry” are placed above the timeline that wraps itself around the exhibition’s outer wall, and alongside images and artifacts pertaining to 9/11. Each vignette is a quotation taken from a variety of speakers (9/11 victims, emergency personnel, government officials, and onlookers) all of whom attempt to comment on and navigate the attacks from the “day of.”

The language of the historical exhibition’s timeline is pragmatic and clinical: “8:46 a.m., North Tower Attack: Five hijackers crash American Airlines Flight 11 into 1 World Trade Center (North Tower). The 76 passengers and 11 crew members on board perish, and hundreds are killed instantly inside the building.” The vignettes, presented like the poetry of Daniel’s Story under spotlights, provide emotionally charged language against the timeline’s explanatory text: “The building roared. / Like feeling vibrations of a speedy locomotive in my kitchen / That’s when the panic set in,” (Greenwald, No Day, 126) describes Kayla Bergeron, a Port Authority employee who escaped the North Tower as the South Tower collapsed. The vignettes often provide the figurative language we associate with poetry (Andrews, 42), and these metaphors may operate as buffers that “absorb the shock [and] filter and diffuse the impact of trauma” (Hirsch, 125) that these spurts of poetically phrased text evoke. The vignettes also help the visitor engage with key moments that the timeline describes. They are text taken from the timeline since “not everyone takes the time to read” every caption board. (Greenwald, interview) In this respect, poetry helps to minimize the effort the visitor must put into engaging with the lengthy descriptions of 9/11, and acts as a caption to other captions.

The vignettes also offer the visitor a tentative escape from the “tape loop of death and destruction endlessly playing” in the historical exhibition); the exhibition features screams, news reels, and images of the Towers disintegrating on repeat. (Kennicott, The Washington Post) One must look “up” to read the vignettes because they are generally placed above the wall displays. In the process, one looks away from the many signifiers of trauma. Just like the juxtaposition of poetry and the pile of shoes in the USHMM, the vignettes of the 9/11 Museum allow the visitor to avoid representations of collective trauma. One vignette creates a particularly noticeable point of relief. Presented on a black wall, without any other media, this poem offers a description from a witness, Hazem Gamal, who describes the chaos he encountered by a subway station in Lower Manhattan on 9/11. The poem is a literal pause as it offers a dark, quiet space away from the main path of the exhibition – it demands the sort of silence one associates with poetry reading, and the emergency exit adjacent to the poem heightens the escape that the poem, in collaboration with its presentation, provides.

Also “off the path” of the historical exhibition is a series of alcoves containing small theaters that present some of the most disturbing material related to 9/11. In one of the alcoves, transcripts of voicemails left by passengers on Flight 93, which crashed in Shanksville, PA after being hijacked, are played to visitors. The alcove is small, permanently dark, and offers benches that allow for eight sitting visitors. The walls are padded for those who stand. As visitors listen to the voicemails left by Flight 93’s passengers, the transcripts of the voicemails appear gradually on a screen accompanied by an image of a plane and a map of Flight 93’s movements. As each transcript appears, their shape resembles a poem.

The nature of the Flight 93 voicemails is inevitably disturbing: It would be tempting to look away from the theater screens if the calls immediately appeared in full. But each line of the “poems” appears gradually. Unlike the lengthy, text-heavy caption boards in other parts of the historical exhibition, the text on the alcoves’ screens does not overwhelm the patrons: it is contained in the poetic structure that each transcript emulates in short, somewhat digestible, bursts of witnessing. Also contained are the voices of emotional callers. At the end of Cee Cee Lyles’ voicemail to her husband (she was a flight attendant on Flight 93), the visitor hears her voice break as she finishes the call: “I hope I’m able to see your face again, baby. I love you. Good-bye.” (Greenwald, No Day, 124) It is difficult not to cry with her, but the poetic structure of the transcript reins in the painful sound of Lyles’ voice cracking with emotion.

The poetry of the Flight 93 alcoves, as well as the other alcoves that feature similar transcripts from the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, serve as captions to the photographs displayed in and around the alcoves. After each set of transcripts is played, photographs of people witnessing the attacks (much like the witness photographs featured at “the ramp” columns) appear on the screens. Like the photos at “the ramp,” we see witnesses unable to verbalize the scenes of atrocity at the Twin Towers and the Pentagon, but the poetically structured transcripts played before these photographs that appear on screen offer language to photographed “silent” witnesses who are clearly stifled by trauma. The poems in the alcoves offer insight into the inner turmoil and actions of the witnesses. The poetry of the Flight 93 alcove is particularly compelling when juxtaposed with the photographs of the Flight 93 alcove. Images of the plane’s debris in the field it crashed in are placed around the alcove and at its entryway. There are no people in these photographs, only the remains of the plane, and a bright red barn in the surrounding farmland. The plane debris is so embedded in the field that the photograph can be momentarily mistaken for a shot of idyllic farmland, but the poetry of the alcove undermines this fleeting tranquility. The poetry places the people of the plane, the voices heard in the alcove, into the images. Like Virgil’s poetry, the poetry of Flight 93 attempts to challenge fragile scenes of beauty that unintentionally occlude the dead.

Why poetry?

Poetry as captions in memorial museums works in collaboration with other communication methods commonly found in memorial museums, like audio, lighting, photographs, artifacts and reenactment in order to clarify and contextualize symbols of past trauma. (Sodaro, 24) Poetry as captions guides us through these exhibitions by “pointing” us in particular directions, challenging the conception that poetry is an esoteric form of language, “something that is not direct or accessible [and rather as language] that needs to be deciphered.” (Greene) In spaces of public history dedicated to collective trauma, language intended to be poetry tends to operate in the conventional ways that a caption operates. Language that evokes poetry tends to emphasize the trope of witness, stressing the affective responses of past trauma.

While poetry mediates an encounter with past suffering, the poem’s distinct structure keeps language contained – the white space surrounding the poem “wraps up” the language within the poem. Poetry can operate as an expressive form of communication, yet a poem’s speaker begins to “speak” before being cut off continuously by the white space surrounding it; poetry is about the expression, but also about the control of language. The white space also sits around the poem like a seal or barrier of protection, as if to remind us that we can only get but so close to the language it contains. Past trauma depicted or signaled to within the poem remains at a perpetual distance.

Poetry and poetical approaches to text may seek to engage us with distant suffering, but what are the implications of using a structure of language that limits and constrains in spaces that aim to create intimacy with a traumatic past? How do we grapple with keeping trauma at a perpetual distance, which may help protect the reader from the full impact of horror, yet may in turn also excuse them from confronting the crux of collective suffering? Poetry as captions in memorial museums, and other spaces of public history dedicated to collective trauma, navigates this dilemma by using poetry to highlight the trope of witness and by transforming the visitor into a prosthetic witness.

Notes

[1] As part of this work, I conducted personal interviews with the USHMM’s Exhibition Experience Manager, Ramee Gentry, and the President and CEO of the 9/11 Museum, Alice Greenwald.

[2] Ms. Gentry of the USHMM was extremely helpful in commenting on the poetry of the museum’s permanent exhibition, but she could not provide comments or documentation regarding the poetry of Daniel’s Story.

[3] The combined display (Finch’s memorial artwork and the Virgil quote) covers the slurry wall that measures 140 linear feet by 34 feet high. (Greenwald, No Day, 20)

References

Anderson, Mark M. “The Child Victim as Witness to the Holocaust: An American Story?” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 14, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1–22. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40207081

Andrews, Richard. Multimodality, Poetry, and Poetics. Routledge, 2018.

Auden, W. H. Selected Poetry of W. H. Auden. Modern Library, 1959.

Boyle, Katherine. “At the Holocaust Museum, Treading Quietly through the Unspeakable.” The Washington Post, August 24, 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/at-the-holocaust-museum-treading-quietly-through-the-unspeakable/2012/08/23/734524bc-eb15-11e1-9ddc-340d5efb1e9c_story.html. Accessed Oct. 15, 2019.

Branham, Joan R. “Sacrality and Aura in the Museum: Mute Objects and Articulate Space.” The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, 52/53, 1994, pp. 33–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20169093.

Caruth, Cathy. Listening to Trauma: Conversations with Leaders in the Theory and Treatment of Catastrophic Experience. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

Dunlap, David W. 2014. “A Memorial Inscription’s Grim Origins.” New York Times, April 3, 2014. Accessed November 16, 2019.

Gentry, Ramee. Personal interview. Nov. 22, 2019.

Greene, Donna. “If Poetry is Puzzling, Who is to Blame?” New York Times, Jan. 4, 1998, p. 3. ProQuest. Web. Nov. 30, 2018.

Greenwald, Alice M., ed. No Day Shall Erase You: The Story of 9/11 as Told at the September 11 Museum. Rizzoli International Publications, 2016.

Greenwald, Alice. Personal interview. Nov. 26, 2019.

Gubar, Susan. Poetry After Auschwitz: Remembering What One Never Knew. Indiana University Press, 2006.

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After The Holocaust. Columbia University Press, 2012.

Huxtable, A.L. “Inventing American Reality,” The New York Review of Books, 39/20 (December 3, 1992), 25.

Kennicott, Philip. “The 9/11 Memorial Museum Doesn’t Just Display Artifacts, It Ritualizes Grief on a Loop.” The Washington Post, June 7, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/ entertainment/museums/the-911-memorial-museum-doesnt-just-display-artifacts-it-ritualizes-grief-on-a-loop/2014/06/05/66bd88e8-ea8b-11e3-9f5c-9075d5508f0a_ story.html. Accessed Nov. 18, 2019.

Linenthal, Edward Tabor. Preserving Memory: The Struggle to Create America’s Holocaust Museum. Columbia University Press, 2001.

McGowan, Matthew M. “In Ancient and Permanent Language: Dialogue in the Latin Inscriptions of New York City.” Classical New York: Discovering Greece and Rome in Gotham, edited by E. Macaulay-Lewis and M. McGowan, Fordham University Press, 2018.

Metres, Philip. “Beyond Grief and Grievance by Philip Metres.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69737/beyond-grief-and-grievance.

“OCME Repository at the World Trade Center: National September 11 Memorial & Museum.” https://www.911memorial.org/connect/911-family-members/ocme-repository.

Radia, Pavlina. “Mobilising Affective Brutality: Death Tourism and the Ecstasy of Postmemory in Contemporary American Culture.” Mobilities, Literature, Culture, edited by M. Aguiar, C. Mathieson and L. Pearce, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, pp. 87-112.

Sodaro, Amy. Exhibiting Atrocity: Memorial Museums and the Politics of Past Violence. Rutgers University Press, 2018. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1v2xskk.

Solomon, Mary J. “A Boy’s Life during the Holocaust: FINAL Edition.” The Washington Post, June 27, 2003, p. T53. ProQuest. Web. Nov. 29, 2019.

Sturken, Marita. 2015. “The 9/11 Memorial Museum and the Remaking of Ground Zero.” American Quarterly 67 (2): 471–90.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, https://www.ushmm.org/collections/ask-a-research-question/frequently-asked-questions.

“9/11 Memorial Museum Welcomes More Than 10 Million Visitors: National September 11 Memorial & Museum.” https://www.911memorial.org/connect/blog/911-memorial-museum-welcomes-more-10-million-visitors.