Moving towards a harmonized heritage tourism approach: an assessment of small museums in Northwest Florida

Sorna Khakzad, PhD; Michael Thomin, MA

The Museum Review, Volume 4, Number 1 (2019)

Abstract Northwest Florida encompasses a variety of cultural resources, including many small museums and historical societies that are dedicated to local heritage tourism and preservation. However, these resources are not widely known and the area is mainly recognized for its white beaches along its coast. In 2016, the University of West Florida’s Florida Public Archaeology Network began an initiative to conduct an assessment of cultural heritage tourism in the region based on the United States’ National Trust for Historic Preservation’s principles for successful heritage tourism. With the cooperation of stakeholders such as local museums and the Panhandle Historic Preservation Alliance, the goal was to identify aspects that can be improved specifically in small museums for achieving a more collaborative and harmonized cultural heritage tourism strategy and museums management. Following the development of criteria for museum assessment and presenting the outcome of the assessment, the current research identifies potentials in the management of these museums and outlines an approach for improving cultural heritage tourism and historic preservation for these museums in the future.

Keywords Small museums; museum assessment; museum management; Florida museums

About the Authors

Dr. Sorna Khakzad is a Research Associate/Faculty at UWF where she is leading a feasibility study to designate Northwest Florida as a National Heritage Area. Sorna has two doctoral degrees in engineering (KU Leuven) and coastal resources management (East Carolina University), and two master’s degrees in historic preservation (KU Leuven) and architecture (Azad University Of Tehran). She has worked on international projects in the Middle East, Europe and the United States, and has been a Think Tank member of European Projects and liaison to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Her research focuses on coastal resources, maritime cultural heritage and strategic planning for museums and cultural heritage entities. Sorna studies interdisciplinary approaches towards the management of coastal and maritime cultural resources for cultural tourism promotion, economic and community development. She has a considerable number of scientific journal publications, academic conference presentations and public talks. Sorna also serves as the President of the Panhandle Historic Preservation Alliance and serves as a member of Trail of Florida Indian Heritage Board of Directors.

Michael Thomin is the manager of the Florida Public Archaeology Network’s Destination Archaeology Resource Center and is a Research Associate at the University of West Florida. He received his M.A. in history/public history from the University of West Florida. Mike has spent over a decade working as a museum professional in public archaeology, is a Certified Guide with the National Association for Interpretation, and has worked on a variety of heritage interpretative and heritage tourism projects across the state. He currently serves on the Trail of Florida Indian Heritage Board of Directors as vice president, St. Michael’s Cemetery Board of Directors, and the Gulf Coast Science Festival Advisory Committee. His research interests include public history, maritime history, public archaeology, museum studies, and heritage interpretation. His published articles have appeared in Legacy, Interdisciplinary Journal of Maritime Studies, and the Journal of the American Revolution.

Introduction

Northwest Florida is home to many nationally significant cultural and natural resources. Nevertheless, while tourism, in general, is a significant portion of Northwest Florida’s economy, the area is less known for its historic assets and more commonly marketed as a beach destination.[1] The recent comprehensive historic preservation study conducted for Florida found that heritage tourism in the state had a large economic impact. For example, it created 75,528 jobs and accounted for $4.13 billion of the state’s annual taxable expenditures for tourism or 63 percent of the annual economic impact that historic preservation has on the state.[2] An initiative under the University of West Florida with the collaboration of local museums and the Panhandle Historic Preservation Alliance recognized the need to assess heritage tourism in this area to identify a strategy that can develop a more attractive and sustainable cultural heritage tourism plan for the area. The regional study used a framework developed by the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) as a guideline for assessment. The NTHP is one of the major sources of reference in the United States for defining and evaluating different aspects of cultural heritage tourism.[3]

The NTHP defines cultural heritage tourism as “traveling to experience the places, artifacts and activities that authentically represent the stories and people of the past and present. It includes cultural, historic and natural resources.”[4] In 1989, the NTHP set up five principles as the foundation for appropriate cultural heritage tourism development and outcomes. Although these principles were established a quarter of a century ago, studies and experiences show that they are still relevant to attract visitors and preserve the unique characteristics of places.[5] These five principles include: 1) focus on authenticity and quality; 2) preserve and protect resources; 3) make sites and programs come alive; 4) find the fit between the community and tourism; and 5) collaborate. These five principles were adopted through the present research to assess the current performance of the small museums in Northwest Florida.

Small museums face challenges or limitations in regards to self-sufficiency, self-sustainability, and sometimes justifying their values.

The term “small museum” is based on Sheila Watson’s definition, where she defined such museums as entities that are developed directly from the community they serve. These museums are community-oriented, their objective is to return the investment locally, and they have different impacts on the community around them. Small museums are not dependent on state and/or institutional funding and governance.[6] Although this independence provides them with freedom of setting their objectives and missions, they also face different challenges or limitations in regards to self-sufficiency, self-sustainability, and sometimes justifying their values. However, studies demonstrate that these museums have many values beyond economic development. These include, but are not limited to, enhancing educational and recreational opportunities, community involvement, developing a sense of pride and identity, and heritage tourism promotion.[7]

Study area and methodology

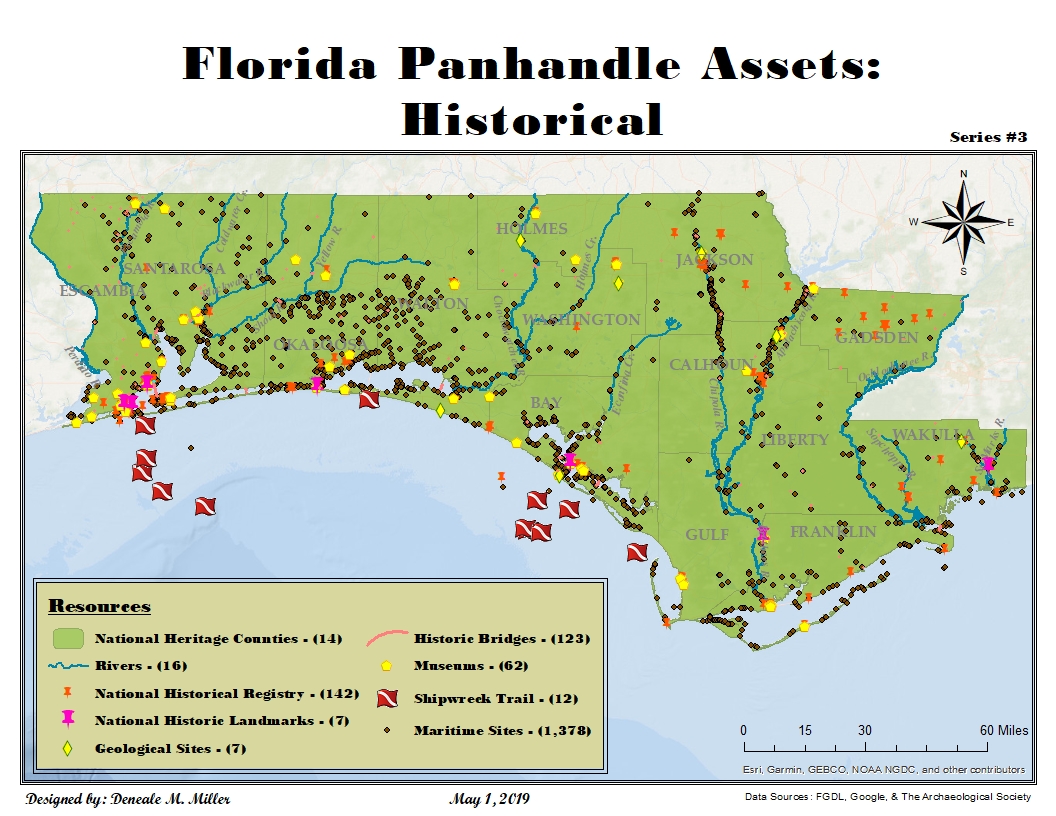

The heritage tourism assessment project focused on the area of Northwest Florida, also known as the Florida Panhandle. The area examined includes thirteen counties with over sixty heritage tourism destinations. Out of these destinations, twenty-one museums fit the definition of “small museums” within the study area. The twenty-one small museums were all visited and their operations were observed by the researchers. The criteria for choosing these museums were their willingness to participate in this project, as well as being considered a small museum.

A mixed methodology of research, including survey and analysis, was used to get comprehensive results. The present research focuses on two aspects: 1) assessing the quality of museums based on the abovementioned NTHP’s five principles, and 2) analyzing the museums’ missions, future visions, and museum manager self-assessment. Two sets of assessment forms were designed for this study. One form was developed to collect data from direct site observations by the researchers, and the other to interview museum managers. In creating both forms, the NTHP’s five principles were the core assessment criteria. To improve the assessment methodology, we referenced previous studies that have used the same assessment method.[8] The site assessment was performed through physical visits to all of the existing study area museums. During each visit, assessment forms were completed by the researchers, who have national and international experience in museum management, historic preservation, architecture, museum collections, interpretation, and education.

An extensive qualitative data set was collected by conducting interviews with museum managers. The interviewees were asked to explain the values of their museum and collection, express their missions and future visions, and state their museum’s needs. In total twelve interview questionnaires were returned and their data was used for comparison analysis and drawing conclusions. In qualitative analysis, we used a Word Cloud on the museums’ mission statements to highlight their goals and visions.

Developing assessment criteria and assessing museums

Applying the five NTHP principles for assessment and learning from the previous studies, we developed a series of criteria for evaluation of cultural heritage tourism and small museums in Northwest Florida.

Quality and authenticity

In modern society with a variety of attractions and distractions, tourists increasingly look for unique and authentic experiences.[9] Heritage tourism is especially beneficial as part of the “experience economy,” and states that create marketing around heritage tourism see the economic impacts first hand.[10] Therefore, the quality of interpretation methods and authenticity of the presented material and programs are crucial in sustaining heritage tourism.[11] The two factors of quality and authenticity are linked together. Visitors expect to have an exciting, engaging, interactive, as well as educational experience.[12] Presentation methods are the sensory, visual, and audio tools applied to display the interpretation. Basic standards and guidelines have been created for the presentation, display, and interpretation of cultural resources at museums and historic sites.[13]

Quality of visit encompasses wider aspects, which fall under “Visitor Readiness.” Visitor Readiness means the consistent delivery of an experience at a museum, an event, or an activity. Based on Hargrove (2010) and Standish (n.d.), Visitor Readiness can be determined by several criteria. We used five main criteria in our museums assessment: 1) Basic operation quality (e.g. contact information, signage, access path, and roads); 2) Openness to public (e.g. convenient operation hours, accessible to all); 3) Staffing conditions (e.g. trained staff, greeters, tours or guides); 4) Exhibition quality (e.g. rotating exhibits, good quality and standard exhibit design, attractive and engaging design, and well-preserved collection); and 5) Programs quality (e.g. diversity of appropriate programs for all ages and groups).

Authenticity and heritage tourism has been the topic of many research studies and debates.[14] Authenticity encompasses several attributes based on the context of the assets, being artifacts or buildings, and their originality and integrity. The PGAV Destination Study states that authenticity in its best form are places where something real happened in history, a natural place untouched by human hands, and is something that cannot be experienced somewhere else.[15] According to the Nara Document on Authenticity and Nara Grid, there are six aspects: 1) Form and design aspects; 2) Material and substance; 3) Use and function; 4) Tradition, techniques, and workmanship; 5) Location and setting; and 6) Spirit and feeling to authenticity.[16] The PGVA Destination study and the Nara Grid were used to evaluate the authenticity of museums’ buildings and collections. Based on our assessment, around 75% of the museums in the study area can be considered authentic in their methods of reproduction, restoration, and interpretation. Several museums can benefit from more guidelines in this respect.

A fit between the community and tourists

To support tourism, cultural heritage tourism should make a community a better place to live, as well as a better place to visit.[17] Previous findings suggest that local museums are successful if they connect with communities, provide opportunities for different groups of people to visit, organize educational and recreational events, and offer work opportunities to the members of their community (both paid and volunteer).[18] Therefore, we used six attributes for this section of museum assessment: 1) Providing programs for different age groups in the community; 2) Providing programs for different ethnicities and cultural groups; 3) Providing programs that designed for special needs people; 4) Reflecting the community values and history; 5) Offering opportunities for local community participation in managing the museums; and 6) Providing genealogy services.

In addition to the direct observation of museums to assess these attributes, managers, staff, and local people were interviewed at each museum. Our study showed that these museums play a strong role in their communities and they have shaped their approaches based on their communities’ needs and values. The museums’ managers are also open to improving the connection between the museum, local community, and visitors.

Preservation and protection

Well-preserved sites and buildings make better tourist attractions and, in return, the income from tourism can help preserve the sites and structures in the long term.[19] Preservation and protection were mainly assessed through four criteria including: 1) Structural stability and building codes; 2) Accessibility and safety; 3) Collection management; and 4) Beautification and aesthetics.[20] Our observations showed that most of the museums are in a good state of building preservation, however, some collections need conservation and restoration.

Collaboration

Collaboration and partnerships among different entities include relationships with political leaders, business leaders, tourism agencies, heritage sites and areas, cultural organizations, and other non-profits such as historical societies, schools, religious entities, and so forth. Partnerships can broaden support and increase chances for success through “packaging” sites and events in the community into a coherent visitor experience.[21] Therefore, in the questionnaire, we asked the museum managers to list their collaborative entities, from local to state to federal.

Although the Panhandle Historic Preservation Alliance tries to connect museums together, and some museums benefit from a variety of collaboration and partnerships, the majority of the interviewees agree that strategies such as developing tourism products, instituting grant programs, and providing marketing and advertising opportunities as a group-approach strategy can help all partners in heritage tourism promotion and community involvement.

Results from specific site observations

The twenty-one small museums in our study area revealed that although many of these museums might have similar goals and missions, their location, operation, and visions of their managers have given them unique manifestations. Considering the five evaluation principles, a summary of specific site observations can show this uniqueness.

Alger-Sullivan Historical Society

The Alger-Sullivan Historical Society was formed to preserve the remnant of the old sawmill town of Century in Escambia County. The museum and the site are mainly a center for local people, where older members of the community are involved in the management of the historical society. This place has given them a sense of purpose, identity, and place attachment. Located in a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places near a state road that connects to a major interstate, the passerby cars can potentially bring visitors to the town.

Apalachicola Arsenal Museum

The Apalachicola Arsenal Museum displays artifacts from the surrounding community and is open to the public. The location of this museum is unique because it is on the campus of a psychiatric hospital at the Florida State Hospital campus in Gadsden County. Aside from interpreting and preserving the historic structure of the Apalachicola Arsenal, the museum is trying to break the stigma about mental illness through exhibits and programming. The museum displays artwork from the patients in the hospital, organizes events for the community, and provides underprivileged children from the school district with opportunities for learning outside the classroom. This museum plays a significant role in public health and raising awareness. During an interview, the museum’s manager Linda Kranert stated, “Mental illness is just that, it’s an illness… it’s nice to share some of their talents to people from the outside so they realize that this is just an illness, like any other illness, you still are a person and you still have value.”[22]

Baker Block Museum

The Baker Block Museum in downtown Baker displays a collection of artifacts from the community and maintains an extensive research library on local history. The research library offers a number of genealogy services as well, including printed materials as well as access to online subscription resources. The museum also plays a role in rehabilitation, as inmates from a nearby prison and newly released prisoners do some of the preservation work for the museum. The museum’s Executive Director Ann Spann stated, “There are a lot of local people who grew up in this area, and I think there is a sense of ownership… it’s our history, our heritage… we are more than a museum, we have a lot of genealogy, school and church histories, so that is important to people for family roots and values, and the core of who they are and where they come from.”[23]

Historical Society of Bay County and Museum

The Historical Society of Bay County and Museum is located in downtown Panama City. The historical society organizes different events and celebrations throughout the year and sponsors a regular lecture series, which brings a wide range of local citizens together. The museum displays artifacts from the community that highlights the maritime traditions of the original downtown area. The society tries to get all the members of the community involved in the museum, advocates for the revitalization of downtown Panama City, and promotes heritage tourism to local historical attractions. This museum plays a strong role in connecting members of communities, and safeguards the sense of identity and pride in the community.

Carver-Hill Historical Society and Museum

Located in a residential area in the city of Crestview in Okaloosa County, this museum is dedicated to the Carver-Hill School, which was a segregated school that opened in 1915 for African-American children. Many of the former students of this school volunteer at the museum and are involved in oral history projects. The museum hosts community and memorial events, such as Carver-Hill May Day Festival and Museum Day, which brings people of the community together and plays an important role to make the African-American community stronger. It also is the regular meeting space for the local chapter of the NAACP. The past president of the board of directors and one of the museum founders George Stakely commented, “The community came together and we built the first museum… We recognize the ones before us… we treasure this building because it brings back memories… We stand high in the community… This building was built for us.”[24]

Holmes County Historical Society

Located in a residential area in the city of Bonifay in Holmes County, the museum displays a wide range of artifacts from local people and items related to local history. According to Holmes County Historical Society’s president Randy Torrance, during the time of the study, the museum was not as active as it should be. He stated, “For the most part the community does not know we are here… we lack publicity and I think that’s true for any organization.”[25] It has about fifty members, half of whom are retired. The community is not very involved in this museum and its activities, but there is potential. For example, within the recent past, the museum’s programming such as a tea party event was attended by hundreds of people in the local community that helped raise some funds.

Santa Rosa Historical Society and Imogene Theater

The Santa Rosa Historical Society maintains a small museum located inside of the Imogene Theater in downtown Milton, Florida. The collection of artifacts on display relates to the downtown vicinity, as well as photographs and paintings from the historic district featuring local businesses and early families who settled the area. The theater is located in a historic district listed on the National Register and offers year-round programming and events. It is used for a wide variety of entertainment purposes to help support the society and its mission of local heritage preservation. The president of the Santa Rosa Historical Society Richard Baldwin states, “It is a place for interconnection of people, industry, and local businesses, which plays a political and social role in the community.”[26]

Heritage Museum of Northwest Florida

Located in a residential area in the city of Valparaiso in Okaloosa County, this museum provides visitors with an appreciation from the cultural resources and many historic industries that built Northwest Florida such as lumber and fishing. It also highlights the community’s military roots in association with Eglin Air Force Base. The museum offers regular field trip programs for students, educators, scholars, and visitors year-round.

Jay Historical Society and Museum

The Jay Historical Society is an organization of members that are interested in researching and compiling local history, and collecting and displaying artifacts, photographs, and other ephemeral materials of the city of Jay and surrounding communities. Volunteers from the rural community run the Jay Museum. The museum has the community involved and interacted, and has over 1,000 members. According to one of the volunteers and members of the Jay Historical Society Tracy Pierce, “This place incorporates into roots, values and identity of the community. It provides opportunities to connect with younger generations by offering fun activities.”[27]

Keith Cabin

The Keith Cabin is a historic house listed on the National Register located in the city of Bonifay in Holmes County. It is locally significant as a rare example of an extant nineteenth-century log cabin. The cabin was restored as a self-guided house museum to show the old way of life of early pioneers in such buildings. According to Nanette Pupalaikis, the president of the Keith Cabin Foundation, “It is a place for the community and for people to come together. This place and its events are the only things that bring people together [in the local community]. People like to preserve the cabin and their way of life, which is something that is slipping away… this is probably one of the only things that the community does where they all come together [here] two times a year, in the Spring and Fall to celebrate as a community.”[28]

Panhandle Pioneer Settlement

This is a living-history museum in Blountstown in Calhoun County with a collection of eighteen historical buildings dating from 1820 to the 1940s. The historic structures were all saved and relocated at the present site. There is also a farm on the site in which the museum produces sugar cane to process into syrup, as well as corn and honey to raise funds and for education. The museum founder and site manager Willard Smith states, “It draws people in here that normally wouldn’t stop… it brings money into the county and also preserves our history because it is so important… this place is about giving back to the next generation, preservation of culture and heritage, preserving memory and way of life.”[29] The living-history museum is operated by local people, mostly senior citizens and gives them an incentive to be active. However, the younger generation is leaving the area due to lack of jobs, which makes the future of this site uncertain.

Native Paths Creek Heritage Museum and Environmental Education Center

Native Paths is a small cultural center operated by the Perdido Bay Tribe of Southeastern Lower Muscogee Creek Indians in Pensacola, Florida. The museum is dedicated to honoring and preserving the tribe’s cultural heritage through art, education, and community service. This place plays an important role to connect people and to raise public awareness about local Native American heritage and culture that remains very much a part of the area’s cultural landscape.

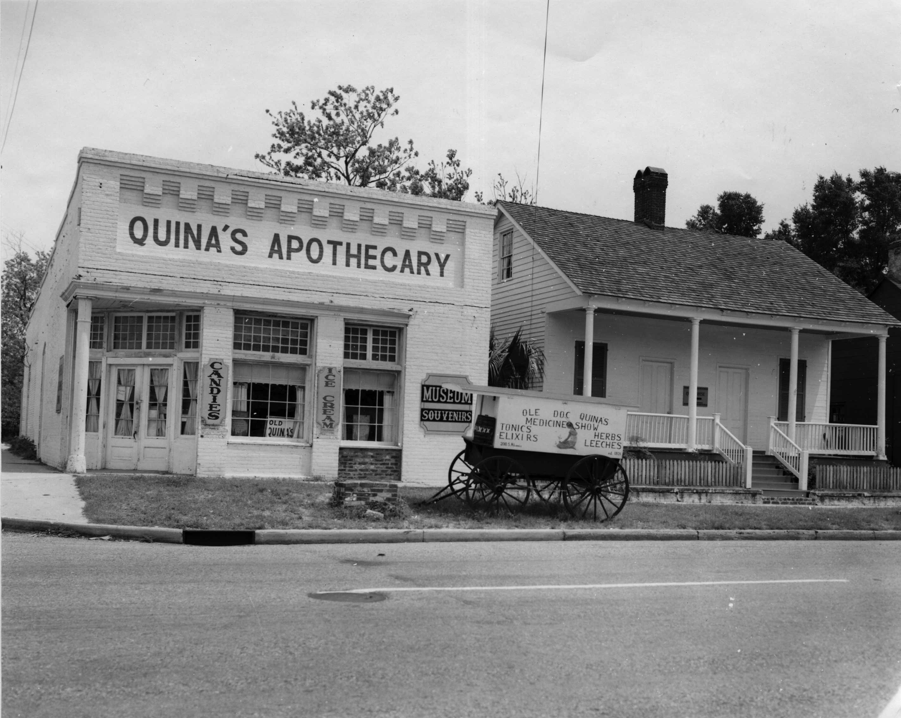

Quina House

The Quina House Museum is Pensacola’s oldest building still in its original location. Constructed in 1810, the living-history museum houses artifacts from Pensacola associated with that time period, and the structure interprets and highlights the history of medicine and industry in some of its displays. The museum is run by the Pensacola Historic Preservation Society, primarily retirees from the community who volunteer their time as docents. According to one of its staff, they have corporate members and sponsors in the local community and the surrounding neighborhood. The museum participates in educational programs and offers special tours for local community groups.

Panama City Publishing Museum

This small museum is located in downtown historic St. Andrews in Bay County and highlights the publishing history of the building. The historic building the museum is housed in was constructed in 1920 as the Panama City Publishing Company, and today the museum hosts historic printing tools, objects, and materials from the period it was used as a newspaper printing facility. It also features artifacts recovered from a nearby shipwreck listed on the National Register that is also a popular artificial diving reef. The museum uses its historic printing machines to produce flyers and invitations for customers as a way to raise money for the museum. According to a staff member, “It is a place of memory and nostalgia. It plays a significant role in sense of community and identity of the city of St. Andrews.”

Walton County Heritage Museum

The historic train station building in downtown DeFuniak Springs houses the Walton County Heritage Museum. The museum displays and collects historic artifacts and objects from Walton County. Volunteers from the community run the museum and organize events. This place connects people to one another and to their history.

Washington County Historical Society Museum

The Washington County Museum is located downtown in Chipley, Florida. The building was originally a train station and a marketplace. The staff are all volunteers from the community. According to the president of the historical society, the local community values the museum mainly as an educational facility for field trips because they are on the curriculum for the school district’s 3rd-grade classes. She also stated that most of their volunteers were motivated by the genealogy services offered through the museum. Another volunteer, who is Native American and donated her substantial collection of educational materials to the museum, stated, “This museum highlights the past way of life and people’s resilience.”[30] She is especially interested in passing her knowledge and artifacts down through the museum because she was diagnosed with some health issues and can no longer teach school children herself.

West Florida Railroad Museum

The West Florida Railroad Museum is located near downtown Milton and is adjacent to a railroad still in use. The structure was originally built as the Louisville and Nashville Depot in 1909 and it is currently listed on the National Register. Also on the museum property are several different types of train cars, a caboose, and an engine cab. Their goal is the preservation, education, and interpretation of the history of trains in Northwest Florida. According to the museum’s director, the local community is highly engaged in this museum and they regularly host private events on weekends. Most visitors are local and the staff consists entirely of volunteers. Most of the volunteers are retired senior citizens, and working at the museum enables them to share their enthusiasm for and hobby of model railroading with the local population.

Apalachicola Maritime Museum

Located in the Apalachicola Historic District and listed on the National Register in Franklin County, this museum promotes and preserves the maritime heritage and ecosystems of Apalachicola with a variety of exhibits and programming. Run by a non-profit organization with volunteer staff, the museum is the only one of its kind in the region that features boat-building programs, sailing excursions, and motorized ship tours as a way to raise money and preserve the maritime traditions of the region.

Destin History and Fishing Museum

The only museum in the area dedicated predominantly to fishing in the Gulf of Mexico, this museum is located off a major highway in the busy tourist town of Destin in Okaloosa County. It features exhibits and equipment related to the local fishing industry, as well as over seventy-five mounts of locally caught fish. Unlike many of the other small museums in the region, instead of focusing on engaging the local community it primarily markets itself as a tourist destination.

Man in the Sea Museum

Operated by the non-profit organization Institute of Diving, this museum is located in Panama City in Bay County. It features indoor exhibits about the history of diving as well as outdoor exhibits featuring underwater diving systems tested at the U.S. naval facility, including SEALAB-1, the world’s first underwater living facility. Its mission is to preserve the history of diving in the area and educate the community and tourists about the significant role its collection played in early diving and testing for the U.S. Navy.

Raney House Museum

Located in Apalachicola, this museum is operated by volunteers from the Apalachicola Area Historical Society (AAHS). Originally constructed in 1838, today the Raney House Museum is listed on the National Register and operates as a house museum that features guided tours led by volunteer docents. The historical society hosts several events throughout the year at the museum to raise funds and to promote itself to the local community, such as “Ghost Walks” at a nearby cemetery and receptions at the Raney House Museum. In 2018, the museum was listed on the Florida Trust for Historic Preservation’s eleven most threatened historic properties in the state, and AAHS members are working on securing grants to make repairs.[31] AAHS are also the primary stewards of the historic Chestnut Street Cemetery.

Results from observations

In general, the small museums in Northwest Florida are displaying the culture, history, and lifeways of people who lived and worked in this area. These spaces provide a vivid image of the history of local industry and development, and the resiliency of people who lived in an area with a harsh climate that continually dealt with the adversity of natural and anthropogenic disasters such as hurricanes, floods, disease, and fire. Yet, despite this, the many cultural groups that occupied this maritime landscape made this area thrive. In addition to telling a significant story, our observations revealed that these small museums play a significant role in their local communities in terms of public health, rehabilitation, resilience, historic preservation, and harnessing the talents and skills within the local population. These museums’ mission statements highlighted some common goals that the small museums in our study areas carry. The most stated goals are enhancing education, honoring heritage and history, informing the future generations, preserving memory, developing cooperation among different entities, and increasing awareness and stewardship for the environment.

Many of these small museums are benefiting from the volunteer work that senior citizens provide. This includes their contribution as docents, researchers, providing and conducting oral histories, writing grants, and preserving the memories of their communities. Some museums that work with special needs people also offer opportunities for these groups a productive way to give back through the various roles volunteers perform at the museums. As observed, some museums benefit from the skills of inmates, who are in rehabilitation programs at the prisons located nearby, in the maintenance and repair of facilities and structures, conservation, and landscaping. Working with different groups of individuals highlights latent talents and skills that not only benefit the museums but also enables these individuals to take an active role in preserving the history and culture of their towns.

Small museums each struggle with two common issues: lack of technical training and reliable sources of funding.

Small museums help the public to become more knowledgeable about their immediate society, and the history of different people living in the same areas. These small local museums provide opportunities and venues for community celebrations and other public events that bring people together. Many small museums offer affordable workspaces for volunteer groups, social service agencies, and other community-oriented organizations. Additionally, by providing spaces for internships or training, the small museums prepare people for employment. The contributions from the small museums in Northwest Florida is tremendous and worth celebrating.

However, these small museums each struggle from two common issues: lack of technical training and reliable sources of funding. While some of these sites have paid memberships to professional museum organizations that offer workshops such as the Florida Association of Museums, The American Association for State and Local History, or the American Alliance of Museums, most do not. This is partially due to the costs associated with attending conferences or workshops (fees, lodging, travel, etc.). While a few museum managers were successfully awarded county and state grants, for those that have not, there was a common sentiment among them such as lack of confidence or knowledge on where to apply for grants.

Moving forward

Based on the outcomes of this study, we concluded that a harmonized strategy for the future that can inspire the small museum managers as well as the local communities could benefit both the historic preservation and heritage tourism in the panhandle area. With the goals of heritage tourism promotion, educational and recreational enhancement, cultural and natural resources preservation, economic development, and most of all community involvement, it was concluded that a National Heritage Area (NHA) designation could fulfill many of these goals. NHAs in the United States are places where historic, cultural, and natural resources combine to form cohesive, nationally important landscapes. Unlike national parks, NHAs are large, lived-in landscapes. Consequently, NHA entities collaborate with communities to determine how to make heritage relevant to local interests and needs.[32]

The studies conducted on National Heritage Areas in the country have shown that there are numerous benefits to the designation. For example, a study on all 49 NHAs estimated that the annual economic impact of these areas was $12.9 billion, the economic activity supports approximately 148,000 jobs, and generates $1.2 billion annually in federal taxes.[33] Branding the area with a national title sparks pride and fosters a sense of identity in the communities. In addition, it encourages historic preservation through technical support and grants received from the National Park Service.[34] The latest reports on NHAs highlight the significant achievement of different NHAs in the country. Examples include achieving a healthy, nature-based tourism economy and environment (Mississippi Gulf Coast National Heritage Area), creating innovative educational programs to learn about history (New Jersey, Crossroad of the American Revolution NHA), reinvigorating a passion for learning about the environment (New York, Erie Canalway NHA), and many more.[35]

Considering the variety of available cultural and natural resources, the uniqueness of many of these resources, and their significance in shaping a cohesive cultural-natural landscape, this study closes with the inspiration of conducting a feasibility study for considering the Florida Panhandle to be designated as a National Heritage Area. We believe the over sixty heritage attractions that currently exist within Northwest Florida fulfill the criteria needed for NHA designation, and this will hopefully provide the small museums with resources they need to improve their attractiveness to tourists, promote more collaboration among different stakeholders, and highlight their values to the local communities they serve. This in return will increase the potential for cultural, natural, and historical resources protection for future generations.

Following the idea of pursuing an NHA designation, during the feasibility study, we followed the motto of “acting as a National Heritage Area, before becoming one.” Therefore, we started testing different management ideas and highlighting how an NHA designation can help the area by creating a harmonized management plan, which can help promote heritage preservation and heritage tourism. For example, through organizing workshops for our partners, helping different entities to recover from disasters, establishing harmonized actions and benefiting from programs, such as establishing trails under Rivers, Trails and Conservation Assistance Program, different entities in the in our area came together to help and learn from each other. Therefore, although an NHA designation is the ultimate goal, we can conclude that a well-planned vision for the future and inspiring collaboration can be an effective way to help our museums preserve and interpret history, and promote their function as tourist destinations.

List of Figures

Figure 1. Florida panhandle historical assets.

Figure 2. Alger-Sullivan Train.

Figure 3. Walton County Heritage Museum.

Figure 4. Apalachicola Maritime Museum.

Figure 5. Destin History and Fishing Museum.

Figure 6. Man in the Sea Museum.

Notes

[1] Visit Florida, Profile of Domestic Visitors to Florida Traveling for Leisure 2016, VISIT FLORIDA Research Department.

[2] Timothy McLendon, JoAnn Klein, David Listokin, and Michael Lahr, “Economic Impacts of Historic Preservation in Florida,” Center for Government Responsibility, University of Florida, 2010, 11.

[3] Cheryl Hargrove, Cultural Heritage Tourism: Five Steps for Successful and Sustainability (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 42-44. Norman Tyler, Ted J. Ligibel, and Illene R. Tyler, Historic Preservation: An Introduction to Its History, Principles, and Practice, Second Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 42-44.

[4] Jamesha Gibson, “Today’s Word: Heritage Tourism,” Preservation Glossary, June 17, 2015, accessed April 26, 2019, https://savingplaces.org/stories/preservation-glossary-todays-word-heritage-tourism#.XKeCQZhKiUk. William Murtagh, Keeping Time: The History and Theory of Preservation in America, Third Edition (New Jersey: John Wile & Sons, 2006), 209.

[5] C. Strickland and C. Hargrove, “Five Principles of Heritage Tourism,” Heritage Tourism Initiative, National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1989. Amy Jordan Webb, “A Decade of Heritage Tourism,” Forum Journal, Volume 13, No. 4, 1999, 4-8. Hargrove, Cultural Heritage Tourism, 51-67.

[6] Sheila Watson, Museums and their Communities (London: Routledge, 2009), 8.

[7] Matthew Evans, “Renaissance in the Regions: a new vision for England’s museums,” The Council for Museums Archives and Libraries, 2001, accessed April 26, 2019, https://www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=12190. Francois Matarosso, “Use or ornament? The social impact of participation in the arts,” Comedia, 1997. Sandra Parker et al., Neighbourhood Renewal and Social Inclusion: The Role of Museums, Archives and Libraries (London: Resource, 2002). Per-Edvin Persson, “Community Impact of Science Centres: Is there any?” Curator: The Museum Journal, 43, 1, 2010, 9-17. Richard Sandell, “Museums as Agents of Social Inclusion,” Museum Management and Curatorship, Vol. 17, 1998, 63-74. Beverly Sheppard, “Do Museums Make a Difference? Evaluating Programs for Social Change,” Curator: The Museum Journal, 43, 1, 2010, 63-74. Deidre Williams, How the Arts Measure Up: Australian Research into Social Impact (Stroud, England: Comedia, 1997).

[8] Shauna Palmer and John Sem, “Strategies for a State Heritage Tourism Industry to Preserve Colorado’s Great Places,” Colorado Heritage Area Partnership, November 1999, accessed April 29, 2019, https://industry.colorado.com/sites/default/files/Cul%20Heri%20Link%206.pdf. Lynn Speno, “Heritage Tourism Handbook: A How-To-Guide for Georgia,” Georgia Department of Natural Resources Historic Preservation Division, March 2010, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.georgia.org/sites/default/files/wp-uploads/2013/09/GA-Heritage-Tourism-Handbook.pdf. Texas Historical Commission, Heritage Tourism Guidebook, The State Agency for Historic Preservation, February 2007, accessed April 29, 2019, www.thc.texas.gov/public/upload/publications/heritage-tourism-guide.pdf. Hargrove, Cultural Heritage Tourism.

[9] Dimitrios Buhalis, “Marketing the Competitive Destination of the Future,” Tourism Management, Vol. 21, Issue 1, February 2000, 97-116. Rodoula Tsiotsou and Ronald Goldsmith, Strategic Marketing in Tourism Services, (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing, 2012), 207-215.

[10] Norman Tyler, Ted J. Ligibel, and Illene R. Tyler, Historic Preservation: An Introduction to Its History, Principles, and Practice, Second Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 284.

[11] Duncan Light and Richard Prentice, “Market‐Based Product Development in Heritage Tourism,” Journal of Tourism Management, Vol. 15, No. 1, 1994, 27‐36; Freeman Tilden, Interpreting our Heritage, Fourth Edition (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 27.

[12] Dallen Timothy, Cultural Heritage and Tourism: An Introduction (Aspects of Tourism) (Bristol: Channel View Publications, 2011), 103-121.

[13] Timothy Ambrose and Crispin Paine, Museum Basics, Third Edition (Canada: Routledge, 2012), 123-145. Paul Caputo, Shea Lewis, and Lisa Brochu, Interpretation By Design: Graphic Design Basics for Heritage Interpreters (InterpPress, 2008). Barry Lord and Maria Piacente, Manual of Museum Exhibitions, Second Edition (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

[14] G. J. Ashworth and P. J. Larkham, Building a New Heritage: Tourism, Culture and Identity in the New Europe (London: Routledge, 2013), 13-30. Brian Garrod and Alan Fyall, “Managing Heritage Tourism,” Annals of Tourism Research Vol. 27, Issue 3, July 2000, 682-708. Hilary du Cros and Bob McKercher, Cultural Tourism: The Partnership Between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management, Second Edition (London: Routledge, 2015). Craig Wiles and Gail Vander Stope, “Consideration of Historical Authenticity in Heritage Tourism Planning and Development,” Proceedings of the 2007 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium, 292-298, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/pubs/gtr/gtr_nrs-p-23papers/41wiles-p23.pdf.

[15] Hargrove, Cultural Heritage Tourism, 51-53.

[16] International Council on Monuments and Sites, “The Nara Document on Authenticity,” Nara Conference on Authenticity in Relation to World Heritage Convention, November 1994, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf. Koenraad Van Balen, “The Nara Grid: An Evaluation Scheme Based on the Nara Document on Authenticity,” APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology, Vol. 39, No. ⅔, 2008, 39-45.

[17] Hargrove, Cultural Heritage Tourism, 14.

[18] Lynda Kelly, “Measuring the Impact of Museums on their Communities: The Role of the 21st century Museum,” Proceedings of INTERCOMM 2006, accessed April 29, 2019, http://intercom.museum/documents/1-2Kelly.pdf.

[19] Donovan Rypkema, Caroline Cheong, and Randall Mason, Measuring Economic Impacts of Historic Preservation, A Report to the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation by PlaceEconomics (Washington, DC; Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, 2011), accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.achp.gov/sites/default/files/guidance/2018-06/Economic% 20Impacts%20v5-FINAL.pdf. McLendon and Klein, Economic Impacts of Historic Preservation in Florida. Daniel Vivian, Mark Gilberg, and David Listokin, “Analysing the Economic Impacts of Historic Preservation,” Historic Preservation Forum, Vol. 14, No. 3, Spring 2000, 49-56. Jim Dulzo, “A Civil Gift: Historic Preservation, Community Reinvestment, and Smart Growth in Michigan,” Michigan Land Use Institute, 2003, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.michigan.gov/documents/hal_mhc_shpo_Civic_Gift_75266_7.pdf.

[20] Anne Grimmer, The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for Preserving, Rehabilitating, Restoring and Reconstructing Historic Buildings, U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Technical Preservation Services Washington, D.C., 2017, accessed April 29, 2019 https://www.nps.gov/tps/standards/treatment-guidelines-2017.pdf.

[21] Hargrove, Cultural Heritage Tourism, 91-106. Texas Historical Commission, Heritage Tourism Guidebook.

[22] Linda Kranert in discussion with authors, September 20, 2017.

[23] Ann Spann in discussion with authors, September 25, 2017.

[24] George Stakely in discussion with authors, August 8, 2017.

[25] Randy Torrance in discussion with the authors, August 8, 2017.

[26] Richard Baldwin in discussion with the authors, August 8, 2017.

[27] Tracy Pierce in discussion with the authors, August 8, 2017.

[28] Nanette Pupalaikis in discussion with the authors, September 20, 2017.

[29] Willard Smith in discussion with the authors, September 20, 2017.

[30] Deborah Bush in discussion with the authors, August 8, 2017.

[31] Melisa Wyllie, “Florida Trust for Historic Preservation Announces 2018 Florida’s 11 to Save at Florida Preservation Conference in Jacksonville,” May 17, 2018, accessed April 26, 2019, https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/5fbefe_f6866ed107e14f1d9e29e59866b1adb9.pdf.

[32] National Park Service, “What is a National Heritage Area?” May 29, 2018, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/articles/what-is-a-national-heritage-area.htm.

[33] Tripp Umbach, “The Economic Impact of National Heritage Areas: A Case Study Analysis of Six National Heritage Areas in the Northeast and Midwest Regions,” 2015, 4-5, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/heritageareas/upload/The-Economic-Impact-of-National-Heritage-Areas_Six-Case-Studies-2015-1.pdf.

[34] Carol Vincent and Laur Comay, “Heritage Areas: Background, Proposals, and Current Issues,” Congressional Research Service, June 4, 2013, 3-4, accessed April 29, 2019, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20130604_RL33462_ef210f5e5a6bd908d1820e73ff59185ec7d7bf46.pdf.

[35] American Alliance of National Heritage Areas, “Connecting the Heart and Soul of American Communities,” Vol. 2, May 2018.